The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us inflationary pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

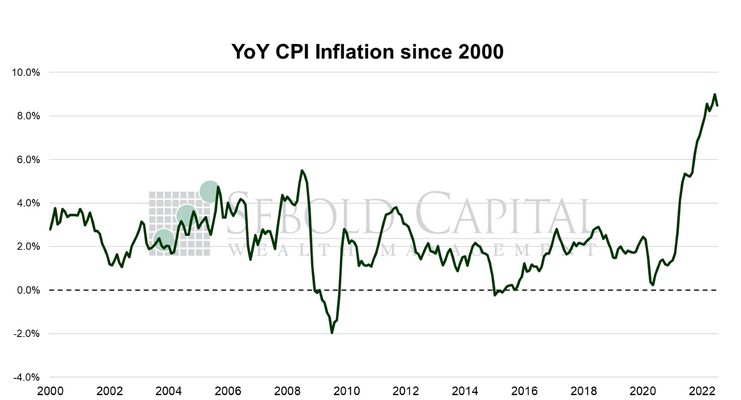

In July, the CPI remained unchanged at 295.3, coming in below market expectations of a 0.4% advance. Year-over-year inflation declined to 8.5%, remaining near its four-decade high but coming in below the expected 8.7% rate. Core CPI—which excludes prices for food and energy and is therefore considered to be less volatile—rose by 0.3%, just below the forecast. Core inflation remained unchanged at 5.9%, which was in line with market expectations.

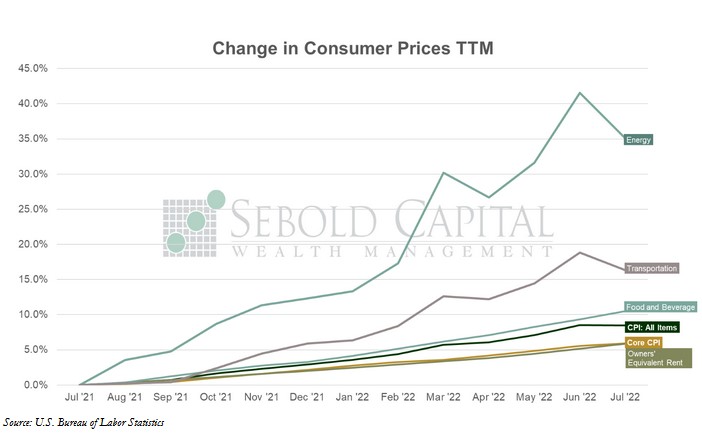

Inflation eased last month from its highest value in over forty years as energy prices declined sharply. The cost of energy, which has been one of the primary drives of the CPI, fell 4.6% last month; gasoline prices were 7.7% lower. However, while prices in aggregate seemed to rise at a slower pace in July, at a more granular level lower energy prices simply offset increases in other categories. Food and beverage prices, another important category in the index, rose by 1.1% on a month-over-month basis—up from 1.0% in June. The rest of report was mixed overall; housing costs increased, but transportation and apparel prices declined. While food and housing costs could continue to put pressure on the price level and cause inflation to keep running hot, lower energy prices seem to indicate that inflation may have finally peaked.

A cooler CPI report eases the pressure on the Fed to raise interest rates. A handful of hotter-than-expected inflation prints led to two consecutive 0.75% interest rate hikes; after this report, a third one seems unlikely. However, the Fed should not let its guard down just yet. It was the inherent volatility of energy prices that led to the high prints in May and June, and it was that same volatility that delivered some relief at last in July. Even if prices remain unchanged for the rest of year—which is a rather unlikely scenario—inflation for 2022 would still end up around 5.1%. Furthermore, while core prices increased at a considerably slower pace compared to previous months, that 0.3% advance annualizes to a 3.8% rate. So far, the Fed has been able to hike interest rates at an accelerated pace without causing any kind of significant disruption to the economy so far; the FOMC should probably not push its luck. Continuing to raise rates 25 basis points at a time—or even 50—can be considered sound policy now that inflation has likely peaked.