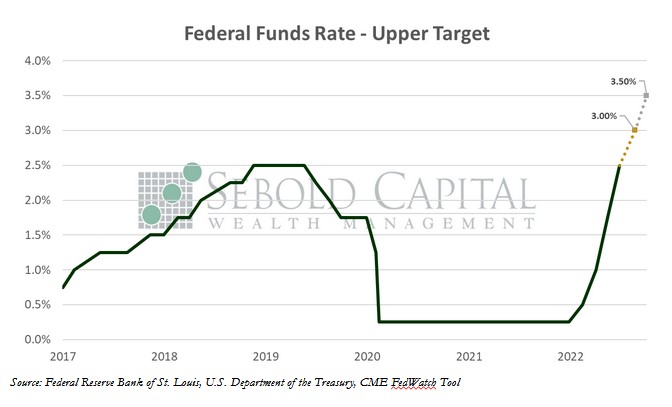

In its latest meeting, the FOMC delivered another unusually large interest rate hike—75 basis points—as it continues to fight the hottest inflation in more than 40 years. That lifted the target for the federal funds rate to a range of 2.25% and 2.5%, the highest since June 2019, and produced a cumulative 1.5% increase in interest rates in less than two months. Unlike the last hike, this one did not take everyone by surprise; three-quarters-of-a-point was the expectation.

One noteworthy aspect of the announcement was the removal of forward guidance on what monetary policy will look like in the coming months. The steps that the central bank will take next will be highly dependent on the data that comes out over the next month.. If inflation remains anywhere near its current level, it is very likely that another 75-basis-point hike will follow in September. Chairman Powell did soften his language around economic activity, although he clearly stated that he does not believe the economy is in a recession.

The first estimate of Q2 GDP was released just the day after the FOMC meeting. It showed a 0.9% contraction on an annual basis—in real terms—against expectations of a 0.5% advance. That is on top of the 1.6% decline in the first quarter. While two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth is not the official definition of a recession, despite political belief, it sure provides an interesting backdrop for tightening monetary policy. What is perhaps more interesting is that nominal GDP not only showed no signs of a slowdown, but actually surged by 7.8% in Q2, up from 6.6% in Q1. That is about double its typical growth rate over the past decade, and it shows that inflation continues to be a problem. If economic activity continues to be driven solely by higher prices, it means that the Fed’s job is far from over.

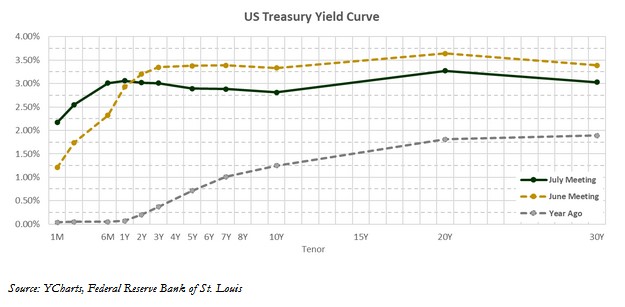

The bond market is already pricing in the expectation that the Fed will cut rates next year, potentially in the face of a real recession. Failure to get inflation under control would almost certainly have a more detrimental effect on the economy than tightening monetary policy. Even if we have avoided an outright recession so far, there is no denying that the economy is decelerating. Consumer spending and manufacturing output have been softening, housing data is weakening, and even the labor market may be losing its luster, as unemployment claims have been ticking up. It is not possible to be in recession with full employment. The employment data will be critical data points for the next 18 months to determine any real economic downturn.

Based on the Fed’s past dovish track record, it would not be an unreasonable assumption to think that the FOMC would cut rates if a recession rears its ugly head—despite how committed to fighting inflation they claim to be. Markets seem to share that view, which can help explain why the yield curve is beginning to resemble a pancake and why equities have rallied despite getting both a significant rate hike and negative GDP growth in less than 48 hours. While we are not in recession now, it still may be in the cards over the next 18 months.