The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us pricing pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us pricing pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

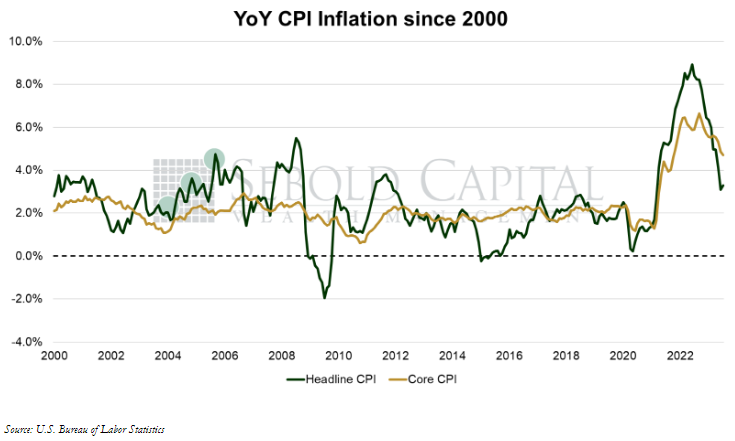

In July, the CPI increased to 304.35 from 303.84. On a monthly basis, consumer prices rose by 0.2%. The annual inflation rate saw a slight increase from 3.0% to 3.2%, the first increase in over a year. However, this was below the expected increase of 3.3%. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy and is therefore considered to be less volatile, fell from 4.9% to 4.7%, also below the expected print. Core prices also increased 0.2% from the prior month.

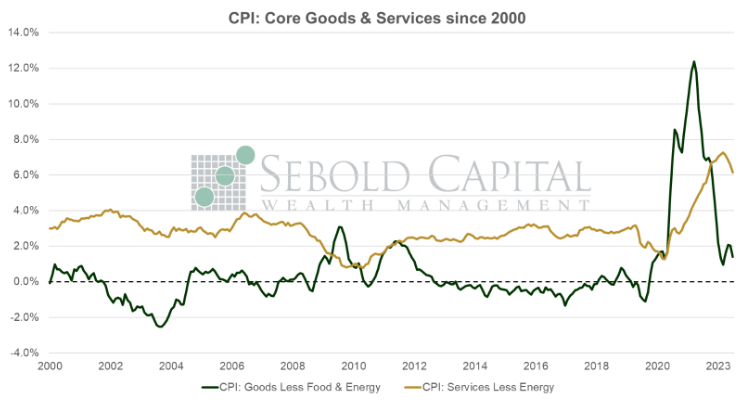

Consumer prices saw moderate increases last month, with the bulk of the increase in headline inflation coming from the housing component of the index. Owners’ Equivalent Rent increased by 0.5% from the previous month, and 7.7% on an annual basis. Food and beverage prices, which rose by 4.8% from the prior year, contributed to the increase as well. These increases in the headline inflation rate were offset by declines in energy, medical care, and transportation prices. Goods prices declined on a monthly basis for the second consecutive time, while increasing at an annual rate of 0.9%. The cost of services increased 0.4% on a monthly basis, and 6.1% from the prior year.

Despite inflation increasing last month, breaking a year-long trend, the overall story does not change much. Headline inflation is a volatile metric, and a single uptick does not necessarily change an overall disinflationary trend. That is especially true considering that money supply has been shrinking for eight consecutive months—although it is drop in the bucket relative to its gargantuan increase in 2020. From a purely mathematical perspective, further increases in the headline inflation rate are not unlikely; inflation has decelerated at such a fast pace that small increases in the underlying data could translate into significant upticks on the annual percentage change. This base effect does not necessarily merit further rate increases, although Fed officials have left the door open to further tightening. Their next meeting in September will not only answer the question of whether they will pause or not, but it will also shed some light on their expectations for the remainder of the year.