The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us inflationary pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us inflationary pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

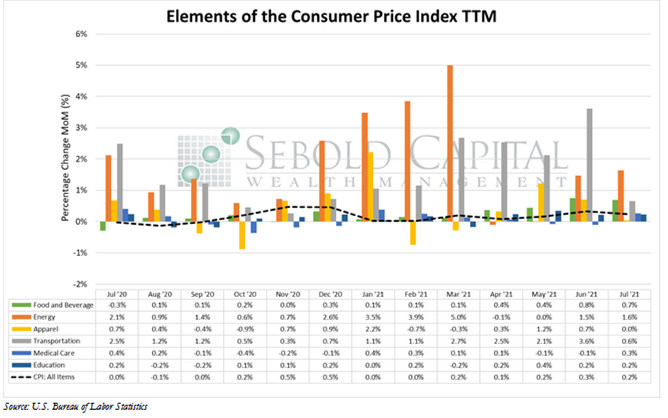

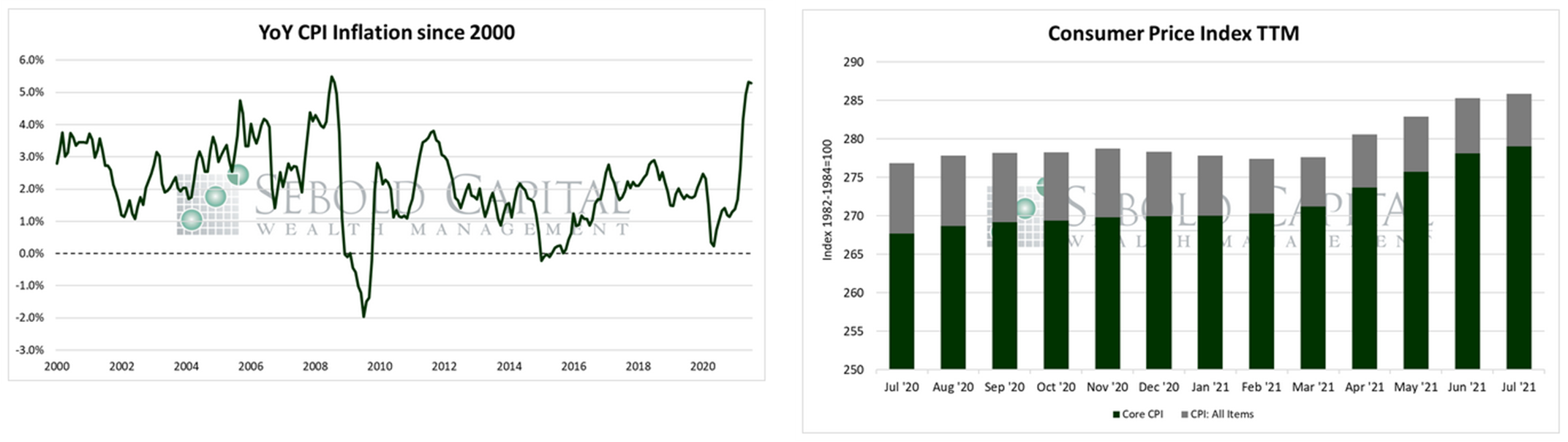

In July, the CPI rose by 0.5% to a level of 272.3. Year-over-year consumer price inflation remained at 5.4%, not exceeding market estimates for the first time this year. Core CPI—which excludes prices for food and energy and is less volatile—rose by 0.3% to a level of 279.1, which puts core inflation at 4.3%, also in line with market estimates.

Last month, consumer prices advanced at a slightly slower pace from the previous month but remained at their highest level in over a decade. Energy costs posted the largest gain for the month, rising by 1.6% from June. Food and beverage prices increased by 0.7%, while transportation costs rose by 0.6%. Used car prices, which had been one of the main drivers for the index, rose only 0.2% last month. Meanwhile, prices for new cars rose by 1.7% and have increased by 6.4% over the past twelve months.

While some proponents of the “transitory inflation theory” may point to July’s CPI as a sign that price pressures have peaked, it is important to remember that the index is an imperfect measure of inflation. For instance, roughly one-fourth of the CPI is made up by what is referred to as ‘owners’ equivalent rent.’ This category, which makes up a larger share of the index than food and energy combined, is mean to represent the imputed cost of owned homes. However, the number is essentially obtained by asking homeowners to estimate how much their residence would rent for under current market conditions. Hardly a method that will produce the most accurate month over months results.

Owners’ equivalent rent has increased a mere 2.4% year-over-year, while actual home prices have soared well past that. Just from January to May, home prices rose by 6.5% according to the S&P Case-Shiller National Home price index. Year-over-year (as of May), home prices surged 16.6%, while owners’ equivalent rent rose 2.1% over the same period. Actual rents are also severely understated in the CPI, as the sub-index that measures rent of primary residence had risen 1.8% year-over-year as of May, while the Zillow Rent Index for All Homes advanced 5.4% in that same time frame. Hard data seems to be in conflict with the soft data.

The way the CPI understates the actual cost of shelter is merely one of the numerous reasons why the index is a less-than-ideal measure of inflation. Other reasons include geometric weighting (automatically reducing the weightings of goods rising in price as an attempt to account for consumer substitution) and using dubious quality adjustments instead of simply measuring out-of-pocket expenses, which is what consumers ultimately feel. Even the Federal Reserve looks elsewhere for its preferred measure of inflation. Yet, the fact that CPI inflation has still managed to surge to 5.4% despite all the index’s limitations should be alarming. CPI inflation is on track to hit 7.0% in 2021 on an annualized basis, so just imagine what the true extent of inflation must be.

August 11, 2021