The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us inflationary pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows us inflationary pressures in the economy. The CPI measures the average price levels of a basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The index starts with a base time period (1982-1984, currently) and shows the overall increase since that time. As with many economic indicators, it can be volatile from month to month, with food and energy prices often leading the volatility.

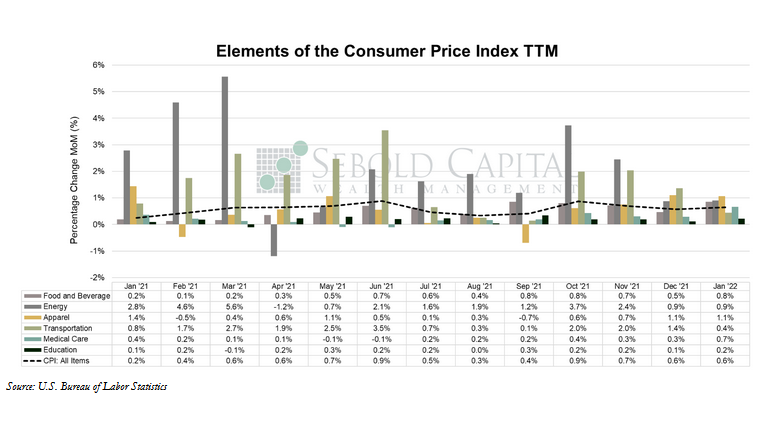

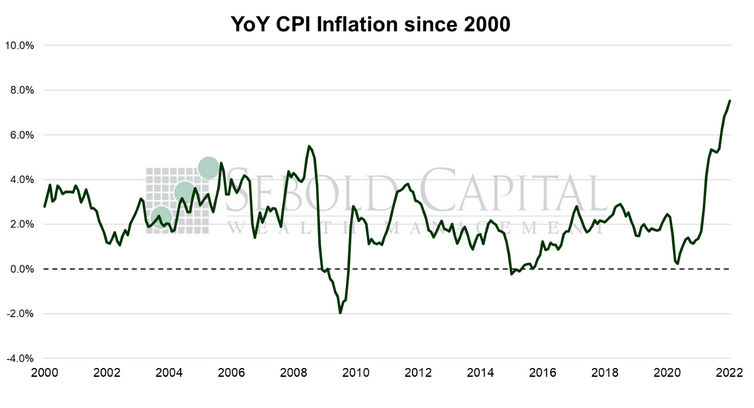

In January, the CPI rose by 0.6% to a level of 281.9, exceeding market expectations by a slight margin. Year-over-year consumer price inflation soared to 7.5%, its highest level since early 1982. Core CPI—which excludes prices for food and energy and is therefore considered to be less volatile—also rose by 0.6% to a level of 286.4. Core inflation surged to 6.0%, likewise hitting its highest level since 1982.

Consumer prices started off the year by rising at the fastest pace in 40 years, as a very loose monetary policy and persistent supply-side constraints continued to put pressure on the price level. Apparel costs had the largest monthly increase in January for a change, rising by 1.1%. Energy prices were the second largest gainer, increasing by 0.9% last month. Food and beverage costs rose by 0.8%, while the cost of medical care saw an unusually large 0.7% increase. Transportation and education saw some of the smallest gains—at least relative to the other categories—rising 0.4% and 0.2% respectively. Owners’ equivalent rent increased by 0.4%, which is a historically large month-over-month advance but still fails to capture the full extent of the higher housing costs and rents faced by consumers; OER rose at an annual rate of 4.1%, while home prices have gone up by double-digits over the same period. Rental leases and mortgages shield consumers from rapid increases in home prices to some extent, but as leases are renewed and people move, the cost of living will likely start to catch up with home prices. The cost of renting a primary residence did increase by 0.5% for the month, the largest advance since 1992, so this is likely starting to happen.

As the next Federal Reserve meeting approaches, uncertainty about what will happen to interest rates remains elevated. While the consensus is certainly that the Fed will increase rates throughout the year, the quantity or extent of those hikes remain anyone’s best guess. For a while, three or four hikes of 0.25% each seemed like the most likely scenario, but increasingly hotter labor market and inflation data has increased the likelihood that the Fed will take a more aggressive approach to tightening—at least according to some. Bank of America sees as many as seven quarter-point rate hikes this year, while St. Louis Fed president James Bullard supports raising the Fed Funds Rate to 1% by July. Likewise, the market seems to be expecting the first hike to exceed 0.25%, with data from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange putting the probability of a half-point or greater hike at 94.7% on the day of the CPI release, up from 24.0% just the day before. Markets also responded to this hotter-than-expected inflation print by selling off treasuries and driving the yield on a 10-year above 2.0% for the first time since mid-2019. However, given the Fed’s notoriously dovish nature, it is likely that the number of interest rate hikes will remain low and that they will not exceed 0.25% each. There will be one more CPI print before the FOMC meeting in March (15-16) where we will see the start of the interest rate hikes. That will have a strong influence on what the rate hike will be. Beware the Ides of March.

February 10, 2022